The Promise of the Premise

Once upon a time, I wanted to write a book about dragons.

No, no, that’s not quite right. Once upon a time, I wanted to write a book about a girl and her dragon, who were fated soulmates — something neither of them chose and which thus caused a lot of problems for them.

For the first several drafts, I attempted to focus strictly on the interpersonal importance of this fact. It took me a long time to consider how the existence of this kind of magical situation would affect the world around the characters. I had a very hard time constructing an interesting plot, because it felt like only two things could happen:

The characters fight their fate bond indefinitely and are unhappy with each other

The characters accept their fated bond and learn to live with each other

In both cases, I felt dissatisfied with how things progressed plot-wise. I always seemed to hit a point at which my characters could move neither forward nor backwards and I would stop writing.

Learning to write this book was a long and difficult process, but I like to think there were two major turning points when I asked:

What if it had not always been this way, and thus might not always be this way? Who is invested in it changing, and who in it staying the same?

How does the existence of dragon soul mates affect the politics, countries, and overall shape of the world outside of my characters and their history?

The first question led me to construct a more interesting primary antagonist, someone outside of the girl-dragon relationship with a vested interest in them working things out and staying together. What I learned is that external forces become mirrored inside. What parts of my character agree with that antagonist? What parts disagree?

And once I had that, I had a more interesting question still: what would my main character do? How far would she go to get what she wanted? And how would those actions of hers – not just her desires – affect the relationship?

The second question (how do dragons affect politics) also led to more engaging outside forces, but via a different direction. It helped me world-build the cities, countries, and polities that exist in the world – to understand how they were shaped by the central question of the book.

When I asked and answered these questions, I was forced to kill darlings and restructure major plot points, but I found it much to the book’s improvement.

Now, I am writing a new book. The premise is a bit more complex, but I am once again asking myself: how do I make sure that the story I construct delivers on the premise? To do that, I am attempting to explore everything the premise promises and allow the plot to fall out from that, rather than assert a plot onto a set of characters.

Here is the premise: If you kill someone with magic, you get their magic.

Okay, so – gruesome, yes? Also fascinating. Imagine what kind of horrible things this would cause in the world! It could be taken in so many different directions — possibly too many different directions — but luckily it came to my mind with a couple of additional shaping questions that led me down a particular path:

What if this also applied to gods? What if the sun was a god? What if someone killed him because they wanted his power?

What if that person subsequently died, leaving the world in darkness?

So, now I have a world in which the sun is gone, and in which powerful magic wielders want to kill each other. Maybe they think if they get powerful enough, they can put the sun back. This creates a very bizarre and very interesting set of external motivators: killing is bad, but bringing the sun back is very, very good. It also comes jam packed with exciting internal problems to assign to characters: a character who wants to save the world for their own ego; a character who wants revenge on someone who killed for this very goal; a character that doesn’t want to kill at all but feels they have to.

Because of these various personalities, I knew near the beginning of my ideating about this story that I wanted some kind of contest to be involved. I then scrapped that idea thinking it was cheesy — and have since come back around to it, for the simple reason that letting people who want to kill each other do so in a strictly regulated way adds tension, structure, and specified pacing to the story. It gives me pockets of time in which the characters can interact interpersonally, develop romantic and sexual tension, and then have to face each other dramatically. It also gives me a wonderful thing to break down completely when it no longer makes sense. Eventually, everything must be questioned.

I watched The Quick and the Dead for research and it did not disappoint. Image description: Sharon Stone as Ellen in The Quick and the Dead, a woman who comes to an old west town owned by Herod, whom she must kill.

Now, this worldbuilding was great and all, but I still didn’t have a protagonist until I asked myself a very, very different question:

What if Reylo. But good. And also gay?

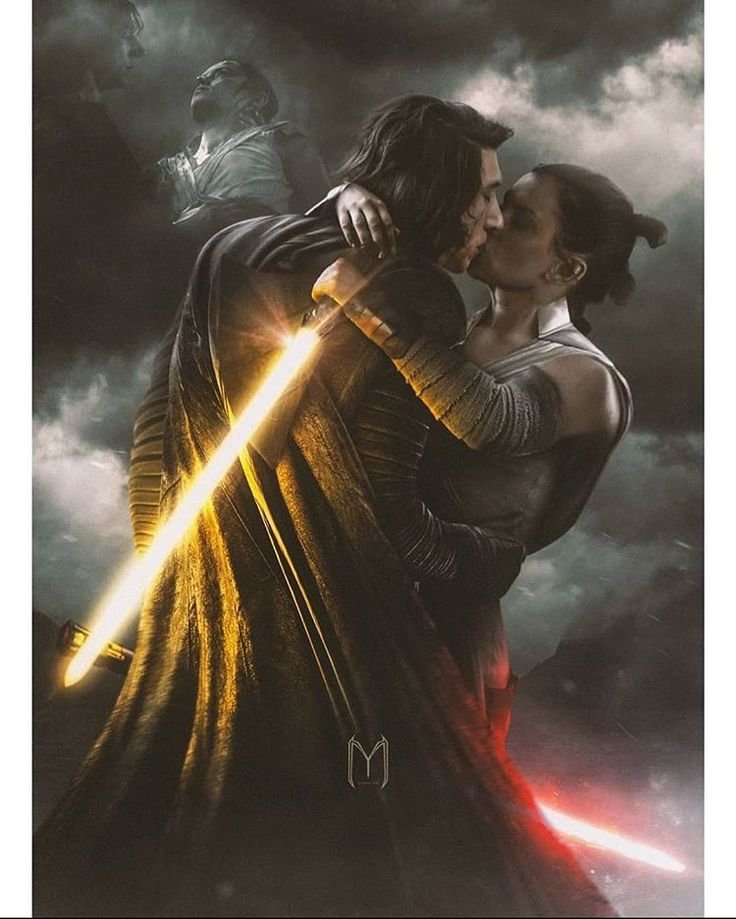

Must a movie really be good? Or is it enough that it be dramatic, aesthetic, and stupid? (Actual image description: Kylo Ren and Rey kissing in front of a stormy sky. They’re both still holding their lighstabers.)

Yeah, I’m sorry, I know I’m trash. I own it gladly.

If you don’t know what I’m talking about, the new Star Wars movies feature two characters, Rey and Kylo Ren, a force-wielder Jedi-type and a sith wannabe, who have romantic and sexual tension. The new trilogy is sadly trash that doesn’t deliver on its premise, but the central question of these two’s relationship compels me. (Sometimes the question is just: can I overlook his atrocities? Perhaps, if he is sexy, and if he has a swordfight with me, I can.)

A picture of me thinking about Rey and Kylo. (Actual image description: Benoit Blanc from Knives Out, saying, “It makes no damn sense. Compels me though.”)

Right, so, here is what happened when I asked this question: I suddenly knew that I had a protagonist who was more of an anti-hero than a hero, who had killed and evaded being killed herself, and who had a foil character who was her opposite in some critical way. Luci sprang from my head practically fully formed: someone who can create light (because that’s what the world needs) but who is very dark inside. Someone whose ability to save the world is bought with blood. And the world lets her do this! Because they need her. They need her to return the sun.

Her counterpart, Nox, has always been a bit more evasive to me. I will watch Daisy Ridley do force shit all day, but I wasn’t satisfied with her draw toward Kylo being one of seeing “the goodness” in him that he so clearly wasn’t interested in himself. I likewise didn’t want Nox to move away from Luci entirely and have them remain enemies, as Alina and the Darkling do. This meant that I couldn’t have her simply be morally pure where Luci is morally corrupt. They are both morally corrupt, but perhaps in different ways.

I don’t know exactly when the thought occurred to me, but at some point I decided that Nox is not merely someone who is opposed to Luci – who comes from “another side” or wants revenge. This all felt a bit too simple. I needed these two characters to be as tied together, as inescapably entwined, as it is possible for two characters to be.

So, I did the obvious thing: I had Luci kill Nox, and then I brought her back to life.

Now Nox is a character who has had her own power stolen, who has been killed, by someone she now has the chance to face and get back at.

And once I had introduced the idea of the undead into my world, a new thought had to come along for the ride: why don’t we bring the sun back from the dead? The dead can walk, can’t they? Let’s just bring him back.

Now we have an interesting world to play in. When is it possible to bring the dead back? When is it not? What happens when the things we think of as final are in fact malleable? What will it mean for Luci when she learns that those she killed might be coming back for her? What if her sins can be sponged out? What if it’s too late for that?

I’d really like to find out.

I’ll let you know when I do.